EM 1110-2-1100 (Part III)

30 Apr 02

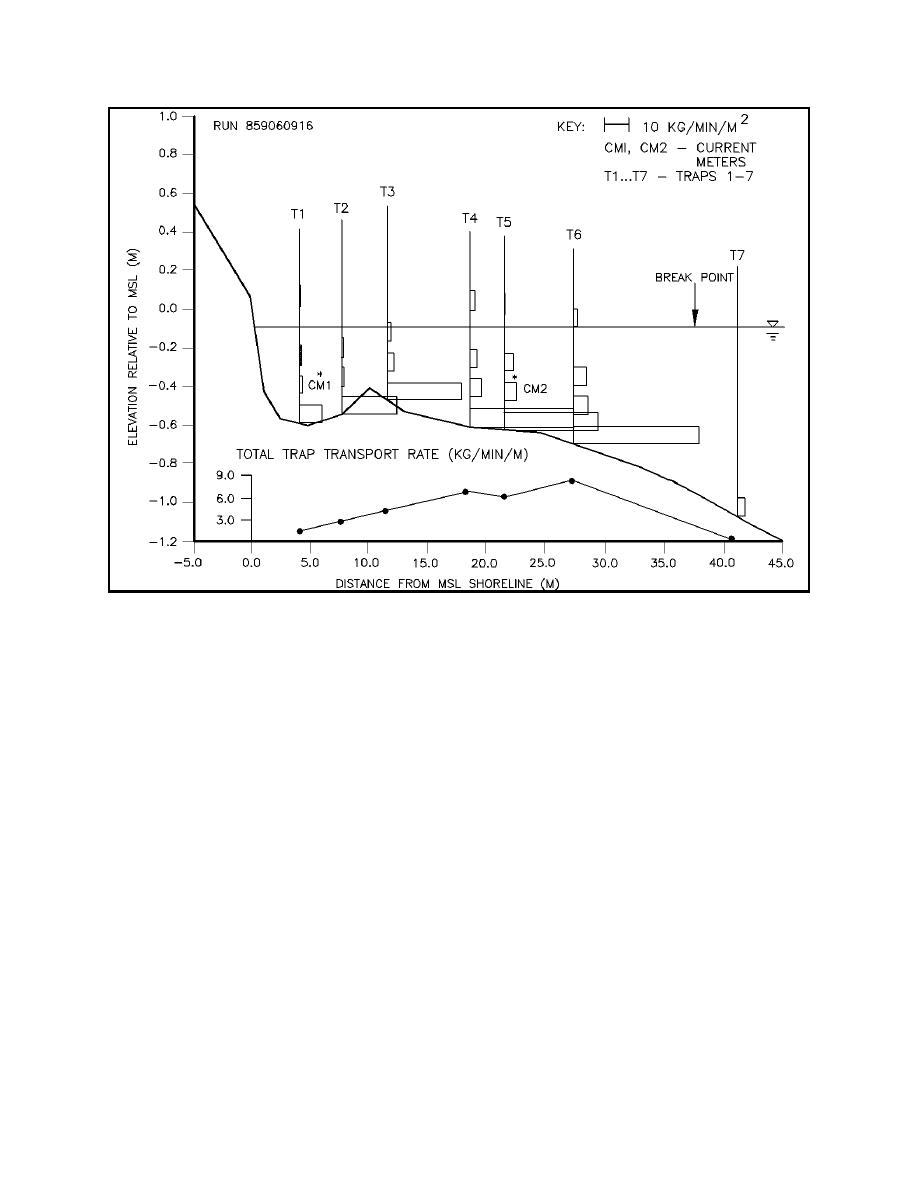

Figure III-2-2. Cross-shore distribution of the longshore sand transport rate measured with traps at Duck,

North Carolina (Kraus, Gingerich, and Rosati 1989)

(2) Qualitative indicators of longshore transport magnitude and direction.

(a) The ability to assess directions of longshore sediment transport is central to successful studies of

coastal erosion and the design of harbor structures and shore protection projects. It is equally important to

evaluate quantities of that transport as a function of wave and current conditions.

(b) Multiple lines of evidence have been used to discern directions of longshore sediment transport.

Most of these are related to the net transport; i.e., the long-term resultant of many individual transport events.

Blockage by major structures such as jetties can provide the clearest indication of the long-term net transport

direction (see Figure III-2-1). Sand entrapment by groins is similar, but generally involves smaller volumes

and responds to the shorter-term reversals in transport directions; therefore, groins do not always provide a

definitive indication of the net annual transport direction. Other geomorphologic indicators of transport

direction include the deflection of streams or tidal inlets by the longshore sand movements, shoreline

displacements at headlands similar to that at jetties, the longshore growth of sand spits and barrier islands,

and the pattern of upland depositional features such as beach ridges. Grain sizes and composition of the

beach sediments have also been used to determine transport direction as well as sources of the sediments.

It is often believed that a longshore decrease in the grain size of beach sediment provides an indication of the

direction of the net transport. This is sometimes the case, but grain size changes can also be the product of

alongcoast variations in wave energy levels and/or sediment sources and sinks that have no relation to

sediment transport directions.

Longshore Sediment Transport

III-2-5

Previous Page

Previous Page