EM 1110-2-1100 (Part I)

30 Apr 02

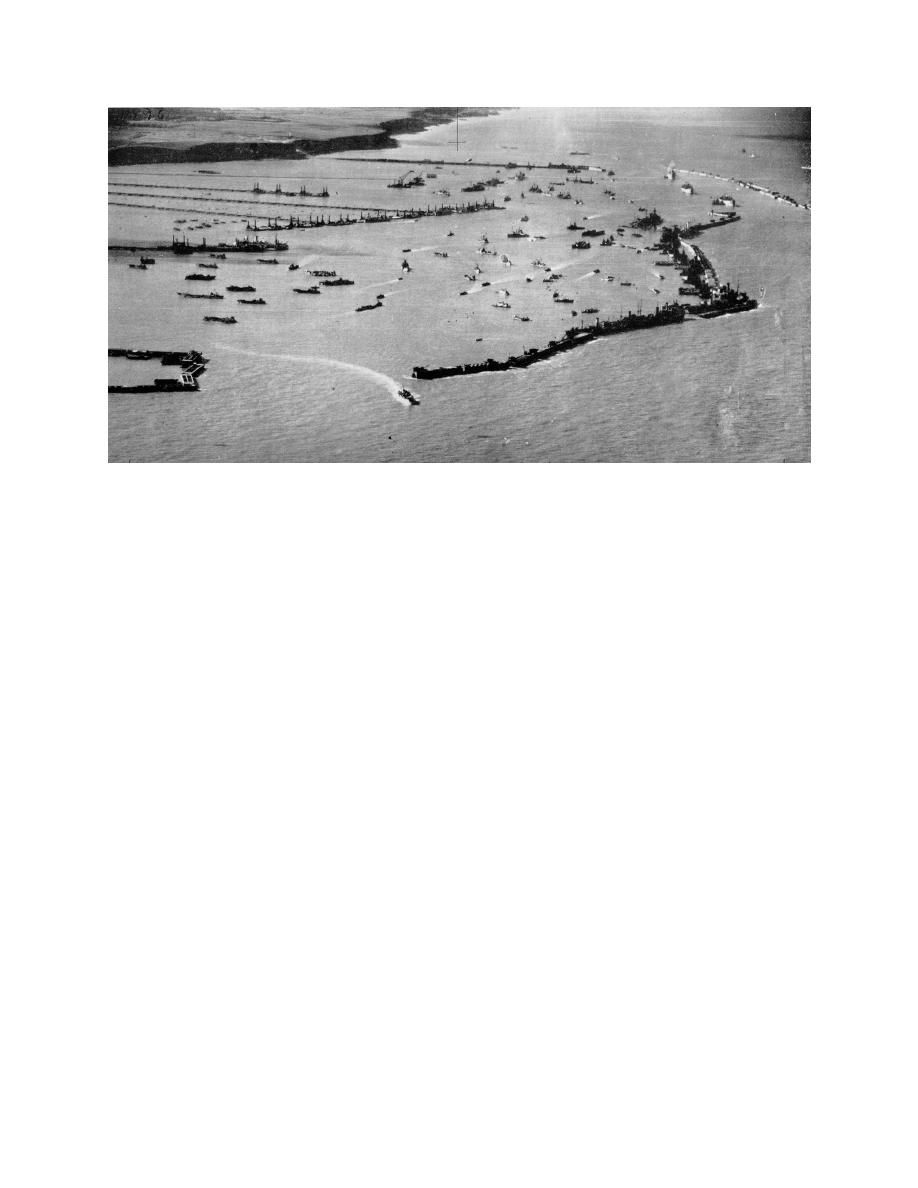

Figure I-3-14. Aerial photograph of the Mulberry "B" Harbor at Arromanches, France, June 1944 (from

Institution of Civil Engineers, London, England, 1948, p. 242)

d. Port operations, Republic of Korea. One of the major amphibious operations in the Republic of

Korea (ROK) was the invasion at Inchon Harbor. The east coast of the ROK is generally rocky sea cliffs,

while the south and west coasts are extensive mud flats with many small conical islands. During low tide at

Inchon, the tidal flats extend at least 50 km offshore and the only approach to the port is a narrow channel

1 to 2 meters deep at zero tide. Extreme tides, ranging from -0.6 meters to +9.8 meters, provided many

engineers their first experience with a sea of water quickly changing into a sea of mud. After the

15 September 1950 amphibious assault, General MacArthur said ". . . conception of the Inchon landing would

have been impossible without the assurance of success afforded by the use of the Seabee pontoon causeways

and piers." The tidal basin and other facilities were relatively intact at the time of the invasion. However,

during the U.S. evacuation in January 1951, the lock gates to the tidal basin were demolished, then rebuilt

after return of the U.S. forces in February 1951 (Wiegel 1999).

e. Port operations, Republic of Vietnam. In Vietnam, the U.S. Navy Officer in Charge of Construction

was responsible for Saigon-Newport and DaNang deep-water ports. Data were collected on coastal

sediments, storms, tides, and waves to plan the dredging of these ports and seven other sites. The Army port

construction section used these data and the Beach Erosion Board's Technical Report No. 4, Shore Protection

Planning and Design, to prepare detailed design of port facilities. The DeLong Corporation's installation

of piers, prefabricated causeway components, and use of self elevating barges also contributed to successful

port facility operations. The sand on many of the Vietnamese beaches was of such character that over-the-

shore operations were almost impossible. Rock, concrete, articulators, pierced-steel planking and other means

attempted to stabilize the sand were serviceable for very limited periods ranging from days to two weeks.

Waves on the foreshore undermined the stabilizing structures and decreased the bearing capacity, resulting

in the structures sinking out of sight. Engineers, drawing on their W.W. II and subsequent experience, used

draglines and blasting to dig nearby coral, crush it, and then place it in compacted layers where the foreshore

had been previously excavated for the purpose. This installation lasted several months with only minor repair

and was judged very satisfactory (Wiegel 1999).

History of Coastal Engineering

I-3-25

Previous Page

Previous Page