EM 1110-2-1100 (Part II)

30 Apr 02

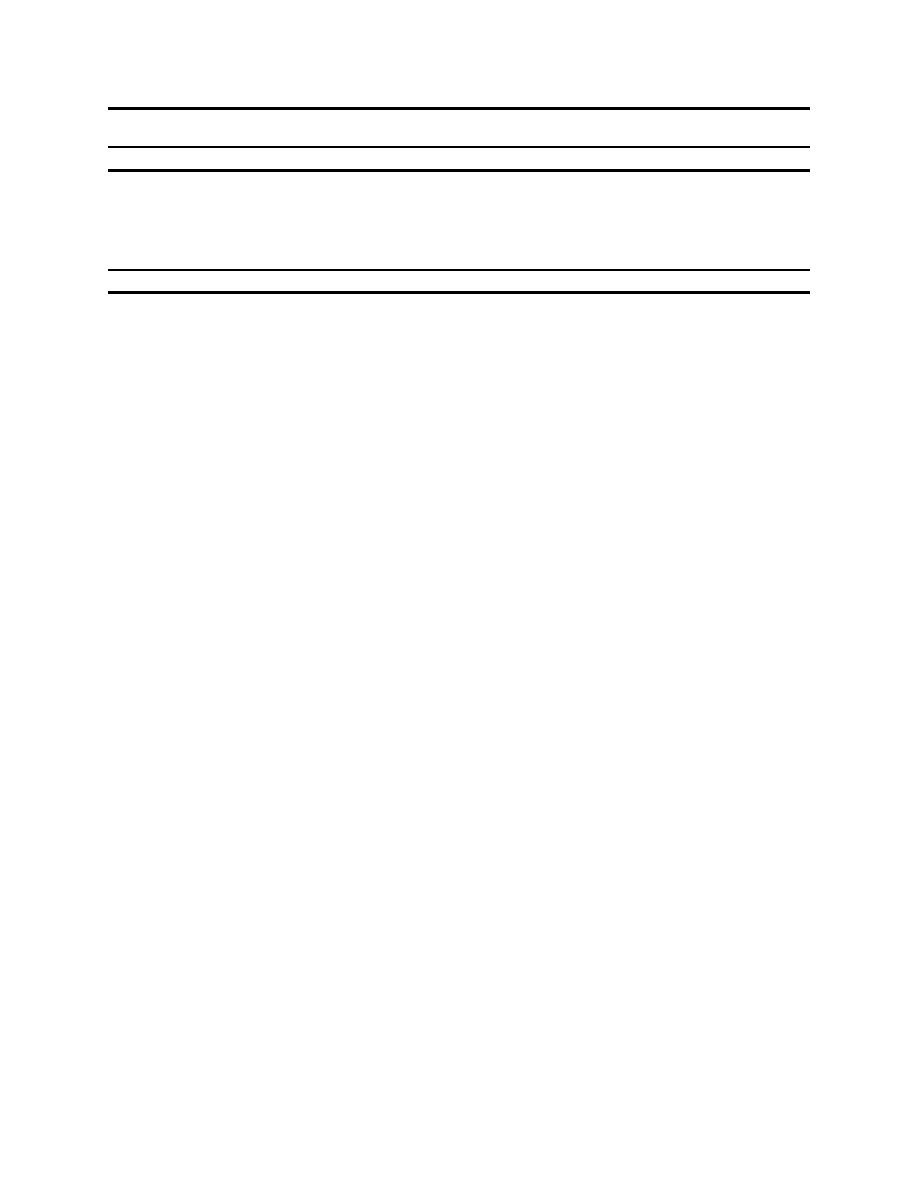

Table II-6-3

Tidal Prism-Minimum Channel Cross-sectional Area Relationships

Location

Metric Units

English Units

Ac = 3.039 x 10-5 P1.05

Ac = 7.75 x 10-6 P1.05

Atlantic Coast

Ac = 9.311 x 10-4 P0.84

Ac = 5.02 x 10-4 P0.84

Gulf Coast

Ac = 2.833 x 10-4 P0.91

Ac = 1.19 x 10-4 P0.91

Pacific Coast

Ac = 7.489 x 10-4 P0.86

Ac = 3.76 x 10-4 P0.86

Dual-Jettied Inlets (O'Brien)

Ac is the minimum cross-sectional area in square meters (square feet) and P is the tidal prism in cubic meters (cubic feet).

(2) Inlet tidal prisms versus minimum cross-sectional area for Jarrett's data is plotted in Figure II-6-9.

(3) Work by Byrne et al. (1980) indicated that for inlets with minimum cross sections less than 100 m2

(1,076 ft2), there was a departure from the relationships developed above. They studied small inlets on the

Atlantic Coast in Chesapeake Bay. Their relationship for area and tidal prism is

Ac ' 9.902 10&3 p 0.61 (metric units)

(II-6-32)

(4) Jarrett's (1976) work pertains to equilibrium minimum cross-sectional areas at tidal channels from

one survey at a given date. Byrne, DeAlteres, and Bullock (1974) have shown that inlet cross section can

change on the order of 10 percent in very short time periods (see Figure II-6-40). This, of course, is due

to the variability in tidal currents and wave energy. A storm may bring a large amount of sediment to an inlet

region, since the inlet tends to act as a sink for sediment and the tidal current may require a certain time period

to return the minimum cross-sectional area to some quasi-equilibrium state. Brown (1928) notes that for

Absecon Inlet, New Jersey, "a single northeaster has been observed to push as much as 100,000 cubic yards

of sand in a single day into the channel on the outer bar, by the elongation of the northeast shoal, resulting

in a decrease in depth on the centerline of the channel by 6 to 7 feet." Sediment changes such as this will

affect the hydraulics of the inlet system, which in turn will remodify channel depth and location of sediment

shoaling.

(5) Adding jetty structures to natural inlets modifies the inlet's morphology. Careful engineering design

can reduce the amount of induced change. For example, jetties are placed so that the minimum cross-

sectional area of the inlet is maintained, leaving the volume of water exchanged over a tidal cycle (i.e., the

tidal prism) unchanged from the natural state. During design of inlet training structures, the question of

appropriate spacing must be answered so that excessive scour does not occur and cause settling or

displacement of the structures. Using O'Brien's formula for jettied inlets, the minimum distance between

jetties can be calculated. Figure II-6-41 shows lines of average depth expected for given jetty spacing and

tidal prism. The data points plotted on Figure II-6-41 describe actual field conditions for 44 inlets. No

attempt was made to analyze or judge whether problems existed at a particular project. For example, a very

large tidal prism with very narrow jetty spacing may develop problems of erosion along one of the jetties or

very high velocities might exist, producing navigational difficulties. Also, if spacing of the jetties is too wide,

the channel thalweg may meander in a sinuous manner, making navigation more difficult and reducing

efficiency, so as to increase shoaling and lead to possible closure. If the same minimum area is maintained

between the entrance channel's jetties that existed for the natural inlet, the tidal prism will be the same, and

tides will flush out the bay behind the inlet as well as they did in the natural state. Actually, a more

hydraulically efficient channel usually will exist at a jettied inlet because sediment influx is reduced and there

are fewer shoals.

II-6-48

Hydrodynamics of Tidal Inlets

Previous Page

Previous Page